By Shelby Tuttle

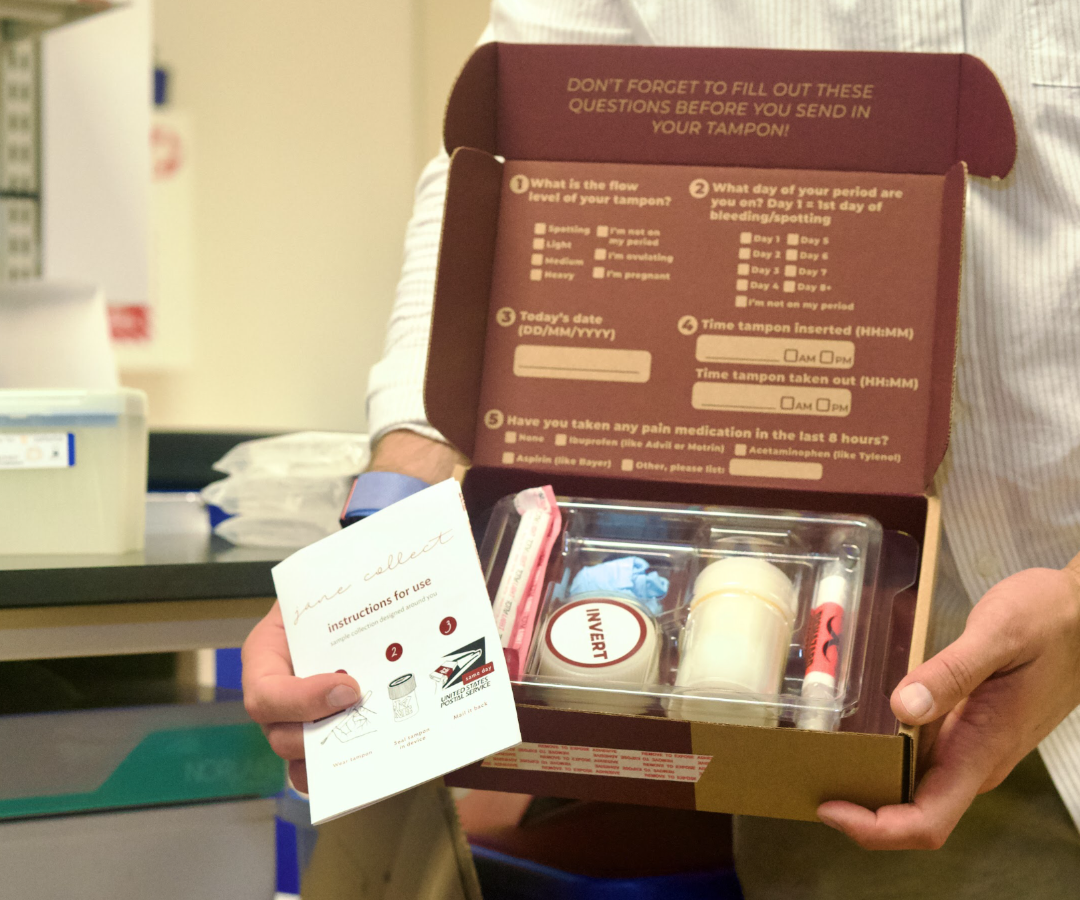

It’s been 10 years since Ridhi Tariyal and her business partner, Stephen Gire, launched NextGen Jane, a women’s healthcare startup that is aiming to revolutionize the way endometriosis is diagnosed. NextGen Jane’s concept revolves around the collection of what Tariyal refers to as “menstrual effluence” — the fluid shed during the menstrual cycle composed of blood, vaginal secretions, and cells from the uterine lining — via a technologically advanced tampon system.

When they first launched the company, Tariyal had no idea what challenges would lie ahead when pitching investors on the merits of this technology. Ideated from a personal experience with a doctor who refused to provide her with testing to gather information on her own fertility, Tariyal originally envisioned a technology that would be able to identify and even predict a myriad of conditions specific to women: polycystic ovary syndrome, preeclampsia, adenomyosis, endometriosis, and a host of autoimmune diseases (80% of all patients diagnosed with autoimmune disorders are women).

“The thing that I care most about right now is that there’s just not great molecular characterization of the conditions that affect women. When you try to understand autoimmune diseases, there’s just not that much of an understanding of the etiology. Why is it that so many women get it?” she questions. “What’s the cause of endometriosis? We don’t really know. How do we change that state?”

Tariyal is level-headed but passionate in her expression.

“The problem that we’re trying to tackle is that we want to make sure that the labeling and the data infrastructure for understanding these diseases that impact women emerges — and it can only emerge with the capital that is large enough to support that novel infrastructure,” she says. “The biggest challenge has been raising the types of checks that novel foundational science takes.”

As such, the team at NextGen Jane repositioned to focus first on what Tariyal calls “a grave unmet need” in women’s healthcare: endometriosis.

“The funding question becomes really important. If we’re capitalized to do this well for one disease, then I’m going to do it well for one disease rather than mediocre for two diseases, or unwell for three diseases,” she says.

She notes that a staggering 1 in 10 women suffers from endometriosis, which can cause a multitude of symptoms that range from diarrhea and irregular periods to debilitating abdominal pain and even infertility. What’s more, in order to just diagnose endometriosis, patients must undergo an invasive laparoscopic procedure in which a surgeon looks for endometrial tissue that has grown outside of the uterus. And statistics show that the average time from the onset of symptoms to the time of diagnosis is a staggering seven to 10 years.

Navigating the Data Gap

Many conclude that the data gap — both in women’s healthcare and pertaining to the disease itself — is why women suffer for so long with the condition before being able to obtain treatment. Many patients are blithely dismissed by doctors, mistakenly evaluated for gastrointestinal disorders, or told that their pain is all in their heads.

Caroline Criado Perez,author of the international bestseller Invisible Women, believes that the data gap begins with how doctors are trained. She notes that “a 2006 review of ‘Curr-MIT’ – the U.S. online database for med-school courses — found that only nine out of the 95 schools that entered data into the system offered a course that could be described as a ‘women’s health course’.”

This gap is prevalent in research, as well. For reference, Criado Perez notes on a 2022 episode of her podcast that in the 14 years prior, the National Institute of Health provided just $176 million in funding for research on endometriosis — a disease that affects 10% of women. During the same time period, hepatitis — a disease that affects just 1% of the population and predominantly more men than women — received $4 billion in funding from the NIH.

This gap is prevalent in research, as well. For reference, Criado Perez notes on a 2022 episode of her podcast that in the 14 years prior, the National Institute of Health provided just $176 million in funding for research on endometriosis — a disease that affects 10% of women. During the same time period, hepatitis — a disease that affects just 1% of the population and predominantly more men than women — received $4 billion in funding from the NIH.

“We wanted to go after something that had both a big imprint on the quality of life and outcomes for women,” says Tariyal.

For decades, women have either been excluded from scientific research or limiting parameters have been put in place to compensate for the “challenges” that women’s hormones introduce into scientific study. In her book, Criado Perez writes that “historically, it’s been assumed that there wasn’t anything fundamentally different between male and female bodies other than size and reproductive function, and so for years medical education has been focused on a male ‘norm’, with everything that falls outside that designated ‘atypical’ or even ‘abnormal’.”

Tariyal notes that a high number of pre-clinical animal studies will often use male models because the “female hormonal cycle introduces a level of variability that is just another thing to take into account.” And while the NIH ruled in 2016 that federally funded studies must incorporate both sexes in animal pre-trials, it’s important to note that plenty of studies are privately funded.

With respect to human clinical trials, the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993 made it illegal not to include women in federally funded clinical trials, but women who are included in trials are often put on very specific birth controls to minimize the variable presented by a woman’s pesky hormonal cycle.

Criado Perez writes, “Female bodies (both the human and animal variety) are, it is argued, too complex, too variable, too costly to be tested on. Integrating sex and gender into research is seen as ‘burdensome’.”

But those burdensome hormones have real consequences for women when it comes to the ingestion of antibiotics, heart medications, antipsychotics, and even antihistamines.

According to Criado Perez, “Some antidepressants have been found to affect women differently at different times of their cycle, meaning that dosage may be too high at some points and too low at others. Women are also more likely to experience drug-induced heart rhythm abnormalities and the risk is highest during the first half of a woman’s cycle. This can, of course, be fatal.”

Says Tariyal, “You’re catching women at different times of the month, so you have no idea where in their hormone cycle you’re catching them. That’s a much tougher challenge that someone should lean into.”

And lean in, she has.

Genomics in Women’s Healthcare

Currently, the team at NextGen Jane has collected over 2,000 tampons from 300 participants in an effort to study each individual’s menstrual fluid over time. Typically referred to as “menstrual effluent” in the medical community, Tariyal intentionally tweaked the verbiage used at NextGen Jane to “menstrual effluence.” The term effluent is often associated with sewage or wastewater, while effluence refers to a substance that flows out of something.

Tariyal — along with a growing component of the medical research community — believes this effluence holds the key to some very critical information about women and, more specifically, the ability to unveil critical information about endometriosis. A fair amount of research has been done on the disease using whole blood from normal venipuncture blood draws comparing biomarkers of people who have endometriosis to those who don’t. Unfortunately, the research hasn’t led to a good understanding of the disease. She believes that’s because the research hasn’t considered the genomic signatures of endometrial tissue.

“There’s a real difference there that undergirds our very scientific hypothesis — and that is in whole blood, you’re getting all of these systemic biomarkers, but in menstrual effluence, you’re also getting access to endometrial lining,” she says. “In whole blood, you don’t have an entire organ that is literally taking its marching orders from the really beautifully coordinated hormonal cascade. However, [women] do have an organ in [their] body that is taking its marching orders from the hormonal cascade. The endometrial lining is exquisitely responsive to the hormonal signaling in your body.”

She goes on to explain that with diseases like endometriosis, if there is a shift in estrogen, it’s going to show up in the uterus — and the endometrial lining — first.

“That’s why we think that it is a much more interesting specimen type to look at for diseases that are impacting [women’s] hormone levels,” Tariyal says.

Tariyal’s background is in genomics, and she is an expert in her field. The 43-year old holds a B.S. in industrial engineering from Georgia Tech, a master of science from MIT, and an MBA from Harvard Business School. Prior to founding NextGen Jane, she led the operation and financial budget of a $10 million genomic endeavor in West Africa for the Broad Institute — a research organization that brings together a community of researchers from across many disciplines from MIT, Harvard, and Harvard-affiliated hospitals. She was also named to the first class of Blavatnik Fellows in Life Science Entrepreneurship as a graduate of Harvard Business School. The five fellows — Tariyal being the only woman — were given the opportunity to work with inventors from Harvard University’s research laboratories to promote the commercialization of important life science-oriented technologies.

“I was always stunned by how genomics transformed cancer care,” she says. “When sequencing became available and affordable, you were able to go back and sequence all these biopsies and develop an entire, profoundly granular, molecular understanding of these cancers — so much so, that you could begin to identify the causative mutations. And once you’re able to identify the causative mutation, that opens up a completely new vista for how you can treat these cancers. It’s amazing, and I’m so glad that’s happening for cancer. That is not happening in women’s health.”

With a current focus on endometriosis, tampons that have been sent to NextGen Jane for other research studies will remain frozen at the company’s research facility in Oakland, California, until the company progresses in its ability to focus on other diseases.

“Part of me knows that I’m going to have to fund some of this foundational building of an understanding of what’s happening,” she says. “And then, disease by disease, bring products to market that transform how these diseases are diagnosed.”

Tariyal notes that ideally, she’d like to do a study with 10,000 patients. Realistically, that endeavor would cost between $50 and $100 million.

“To do this right, [we want] to have age-matched ethnicity cohorts because [we] need to establish what a typical menstrual cycle looks like for these age groups within these ethnicities as a starting point. And then [we] can begin to establish against that typical cycle what disease states look like,” she says.

To Market They Go

She estimates that NextGen Jane is about two years from going to market — first as a diagnostic tool for gynecologists, followed by a hopeful approval as a direct-to-consumer test much further down the line.

“There are layers and layers and layers of regulatory requirements that you have to meet in order to have a clinical diagnostic that is off the shelf that [people] can buy at a pharmacy. We want to get this in the hands of women as fast as possible. And if that means selling to the provider, then [we’ll] sell to the provider.”

And although selling to providers would still leave an endometriosis diagnosis in the hands of healthcare gatekeepers, it would effectively remedy the need for a woman to endure a costly — and invasive — exploratory procedure with an average recovery time of one to two weeks. Tariyal believes that it would also serve to educate gynecologists about the disease on a greater level and shorten the time to achieve diagnosis.

And although selling to providers would still leave an endometriosis diagnosis in the hands of healthcare gatekeepers, it would effectively remedy the need for a woman to endure a costly — and invasive — exploratory procedure with an average recovery time of one to two weeks. Tariyal believes that it would also serve to educate gynecologists about the disease on a greater level and shorten the time to achieve diagnosis.

“One thing that we can do as a company to help make this [known] earlier, is educate GYNs. If you think about a woman that comes in, and she has this debilitating pain — a GYN has a certain (limited) set of tools that they can use to work this up. Currently, the diagnosis sits in the hands of surgeons who are skilled in laparoscopy,” she says. “But now imagine if a GYN has in their toolbox a tampon that they can send [her] home with and mail it in, that will [provide] an indication of whether or not this could be endometriosis. That’s game changing.”

Game changing, indeed. But before NextGen Jane can get the test to market, additional research must be completed. Tariyal informs me that her first intent is to target women who are struggling with infertility.

“We established a genomic classifier that is different in women who have endometriosis versus those who do not. When you look at IVF clinic [patients], an absurdly high number of women just have undiagnosed endometriosis,” she says. “But before a provider will feel comfortable prescribing a test for a particular condition, they want to know how well it works in that intended population. We need to establish how well it works in women who have infertility.”

She continues, “Right now, we are recruiting women who have struggled with infertility specifically and either know that they have endometriosis or know that they do not have endometriosis.”

She clarifies that participants can currently be struggling with infertility or have struggled with it in the past, and that the team hopes to get 300 more participants for this next round of research. Tariyal and her team have worked to recruit clinical study participants by reaching out to fertility clinics across the country but still have a significant need for additional women to enroll.

“This only happens by women raising their hands and saying, ‘I’ll be part of your research,’ and we’re so grateful for that,” she says.

And while she notes that it’s an exciting time to be in women’s health because there seems to be a new interest in it — “there has not been much interest in the past,” she quips — she comes back to the fact that NextGen Jane must first prove that there’s a need for this type of technology before it will ultimately receive the funding and attention it deserves.

But how is a need determined? Some may argue that because there’s already a way to diagnose endometriosis — albeit an invasive and costly one — that a test to more easily diagnose a condition affecting only women isn’t warranted, summarizing the systemic beliefs that have prejudicially compromised womens’ health for decades.

For Tariyal and her colleagues in the menstrual health field, the need is incontrovertible.

“The time that I spoke to a 23-year-old girl who had a hysterectomy because that’s what her doctor said was necessary… the stories are very hard for me to share,” she says. “Describing how hard it is to navigate this… it’s not even just hard. It’s hard from every perspective — from dealing with investors to dealing with layer upon layer of problems and complexities in trying to bring something like this to market. The thing that makes it really enjoyable and you know, keeps us going, is just the conversations with women. Every time I hear a story about a woman and what she had to deal with to find an answer, I’m electrified. What I’m dealing with is nothing compared to what these people are dealing with.”

For more information on NextGen Jane and to enroll in one of the company’s current clinical studies, visit www.nextgenjane.com/clinical-studies.