The quietly impactful legacy of one of our nation’s most esteemed environmental pioneers

David M. Brown

. . .Earth’s the right place for love:

I don’t know where it’s likely to go better.

—Robert Frost, Birches

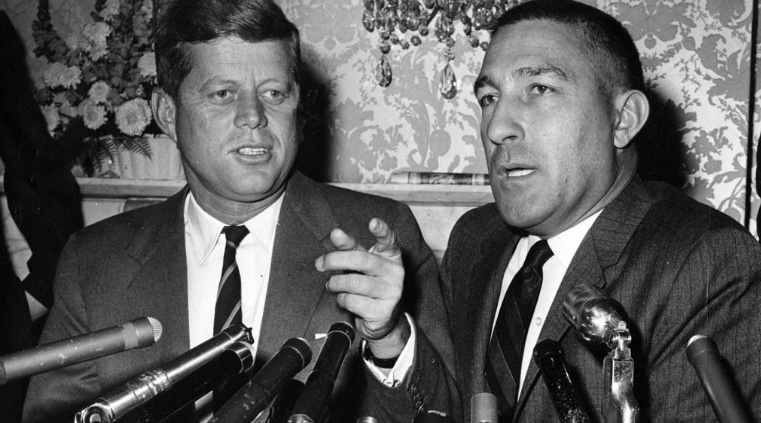

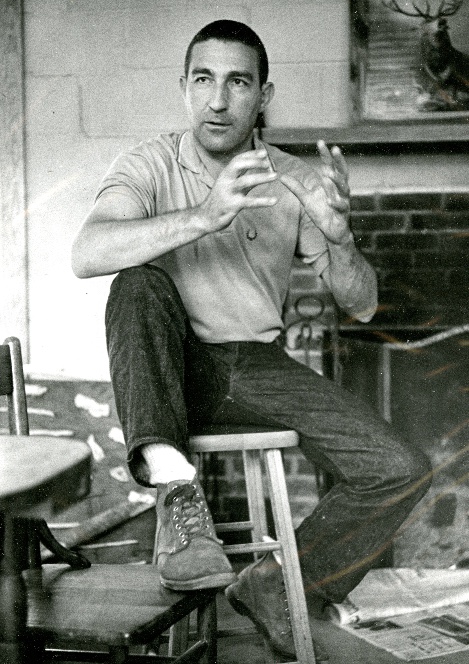

This Earth Day, remember Stewart Lee Udall (1920–2010), the Arizona-born Department of Interior Secretary who served from 1961 to 1969 for Presidents Kennedy and Johnson. Six decades ago, Udall fought for environmental stewardship and justice and was one of the first public officials to warn about climate change.

On Jan. 31, what would have been Udall’s 103rd birthday, noted author and documentarian John de Graaf premiered his 90-minute film Stewart Udall and the Politics of Beauty at the Interior Department building in Washington, D.C., which is named for Udall.

The film’s debut was attended by several notable figures who appeared in it, including former Arizona Governor and Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt. He credits Udall with fundamentally changing how we perceive our environment, establishing a “transcendental attitude.”

Current Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland spoke at the event and told the group that her love for the outdoors was inspired by trips her family took that were like those the Udall family enjoyed, as shown in the film.

“I learned through those experiences how these lands sustain our health, communities, and our sense of wonder. Conservationists like Stewart Udall helped make those formative experiences possible for my siblings and me and, of course, for countless others,” she said.

But filmmaker de Graaf is concerned that many young Americans do not know about Udall, known as “Mr. Conservation” in his time.

“He’s just a remarkable, not only state figure but national and international figure,” he says. “He was an ambassador for the United States for conservation and parks all over the world.”

When we remember the words and accomplishments of other environmental exemplars such as Sen. Gaylord Nelson, the “father” of Earth Day; John Muir; Aldo Leopold; A.B. Guthrie; Rachel Carson; Teddy Roosevelt; David Brower, the founding Sierra Club director; and America’s prophet of nature, Henry David Thoreau, certainly Udall’s name deserves to be considered among these giants, too.

Acts of Concern

De Graff believes that for Arizonans, Udall forms a triumvirate of political luminaries, with Barry Goldwater and John McCain. And, for all Americans, his legacy as interior secretary may be unprecedented.

“The Udall legacy is absolutely huge. So much great environmental legislation that we now take for granted was introduced by him and pushed by him through Congress,” de Graaf says, who was first impressed by Udall when he interviewed him in 1988.

Udall’s leadership, anchored in principle and bipartisanship, helped realize these acts: Clean Air; Water Quality; Clean Water Restoration; the Land and Water Conservation Fund; Wilderness; Highway Beautification; Endangered Species Preservation; Wild and Scenic Rivers and National Scenic Trails; Pesticide Reduction and Mining Reclamation; Solid Waste Disposal; and National Historic Preservation.

While he was interior secretary, four national parks were established: Canyonlands, Utah; Redwoods, California; North Cascades, Washington; and Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, Virginia. Six national monuments and eight national seashores and lakeshores were also established, including Point Reyes National Seashore in California and Cape Cod National Seashore in Massachusetts. Furthermore, his work also created nine national recreation areas, 20 national historic sites, and 56 national wildlife refuges, along with the designation of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail as the nation’s first national scenic trails. Notably, he also helped ensure the restoration of Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., and established the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation.

While he was interior secretary, four national parks were established: Canyonlands, Utah; Redwoods, California; North Cascades, Washington; and Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts, Virginia. Six national monuments and eight national seashores and lakeshores were also established, including Point Reyes National Seashore in California and Cape Cod National Seashore in Massachusetts. Furthermore, his work also created nine national recreation areas, 20 national historic sites, and 56 national wildlife refuges, along with the designation of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail as the nation’s first national scenic trails. Notably, he also helped ensure the restoration of Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., and established the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation.

“While [Udall’s public career] takes place in the . . . 1950s and ’70s, it is absolutely current to the issues that we face today and to provide us inspiration that we can actually make the changes we need to make,” says de Graaf, a Seattle resident who grew up hiking and backpacking in the Sierra Nevada region in California.

De Graff has been producing award-winning documentaries for 45 years, mostly for PBS, and written three books.

“With the story of one person, we can tell a huge story of the American history of that period, too. I hope the film makes that clear to all its viewers,” he says.

“Prescient” is Brooks Simpson’s short description of Udall. An ASU Foundation professor of history in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts at Arizona State University in Tempe, he specializes in political and military history, as well as the American presidency.

“He was forward-looking, anticipated problems, and acted to address them in a timely fashion. All too often, it is not until an environmental problem hits us in the face that we begin to think about what to do, and then our options are limited, costly, and all too often fall short,” Simpson says.

“In terms of public figures, Udall is at the forefront of the environmental movement in the same way Theodore Roosevelt anticipated the need for widespread conservation initiatives,” he adds. “Stewart Udall believed that the government could make the lives of people better and focused on issues of common concern. He led quietly, yet his achievements are all around us.”

Udall’s legacy is “impactful. [His] body of work was extraordinary. The legislation championed by him are classic, timeless, and bipartisan legislative frameworks that are still in effect today. That is the true measure of an impactful leader,” says Chandler’s Vada O. Manager, an entrepreneur/investor who was the executive producer for the film.

A staff member for Gov. Babbitt, Manager is the first and only African American to serve on the Arizona Board of Regents, and was also the first to serve as a press secretary when Gov. Mofford appointed him in 1988.

America the Beautiful — for Everyone

The son of a Mormon rancher, Udall was born in 1920 in a town called St. Johns on the Lower Colorado Plateau in northern Arizona. His brother Mo would joke that the town was so small you could affix the entering and exiting signs to the same post.

Founded in 1874 by Hispanic pioneers, the mile-high rural town is near the Petrified Forest National Park, Painted Desert, and Mogollon Rim, the 7,000-foot high Ponderosa pine-studded escarpment that cuts across northern Arizona and New Mexico. This dramatic setting gave Udall an early appreciation for natural beauty and commitment to environmental sensitivity, de Graaf’s film points out.

He attended Gila College and the University of Arizona, then completed church missionary work back East, served in World War II as a waist gunner in Europe on a B-24 bomber, and returned to U.A. in Tucson to star in basketball and complete his law degree. After marrying Ermalee Webb, he opened a law practice in 1949.

He attended Gila College and the University of Arizona, then completed church missionary work back East, served in World War II as a waist gunner in Europe on a B-24 bomber, and returned to U.A. in Tucson to star in basketball and complete his law degree. After marrying Ermalee Webb, he opened a law practice in 1949.

Three years later, Tucsonians sent Udall to Congress, where he served three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. During his final term, he led the Kennedy presidential campaign in Arizona. Sixteen years later, he coordinated a presidential campaign for his brother Mo.

At UA, Udall demonstrated his commitment to racial justice as well, years before the issue became nationally prominent. He joined the Tucson NAACP in 1947 and with Mo fought to integrate the UA cafeteria. In 1962, he integrated the National Park Service rangers. As a result, Robert Stanton became a ranger and went on to become the only Black director of the National Park Service.

That same year, with Kennedy’s assistance, he forced the Washington Redskins professional football team (now the Commanders) to hire black players, as the team’s home stadium was under the Department of Interior’s control. A year later, he approved the permit for Martin Luther King’s transformative March on Washington, where the future Nobel Peace Prize laureate delivered one of the great speeches in national history, “I Have a Dream.” And, five years later, he broke with the Mormon Church because of its ban on Blacks in the priesthood.

In the same spirit, he sought to expand self-determination for tribal nations. In 1966, he prevented the federal transfer of lands to the state of Alaska to ensure that native Alaskans would not lose them. He supported Navajo miners, as well as the “downwinders” in Nevada, who had been adversely affected by atmospheric atomic testing in the desert.

Today, the country is unquestionably polarized and rift politically. Udall’s early mastery of bipartisanship is particularly appropriate in these times. His politics were based on his concept of the “Economics of Beauty” – an appreciation of our resources viewed as life-affirming assets, not monetized real estate. Protected lands were part of the community, not a commodity, and certainly not the interests of a singular party.

“Udall was a creature of a different time and place when it came to the political environment in which he operated,” notes Professor Simpson. “His Arizona roots helped him understand the importance of bipartisanship, and he understood the costs and counter-productiveness of turning challenges and problems into fodder for partisan bickering and stalemate. He was more interested in results than in taking credit for them, which may help explain why many people are unfamiliar with his achievements, even though they benefit from them every day. The world’s a better place because of Stewart Udall.”

De Graaf adds, “In many cases, sometimes his strongest supporters were Republicans, and a few of his strongest opponents were Democrats, including Jim Crow Democrats from the South. He proved that we could come together as people, and we could make these decisions that benefited generations to come.”

As all humans do at times, Udall erred. The film reveals how he regretted supporting the Glen Canyon dam in 1957, which inundated some of the West’s most sublime canyon wilderness. However, he later opposed two additional Arizona dams in the Grand Canyon a decade later.

His befriending of various authors, poets, artists, and influencers – such as Rachel Carson, Ansel Adams, Robert Frost, and Lady Bird Johnson – also helped him advance the concepts of conservation, beautification, and stewardship. During his life, Udall wrote nine books including the environmentally-focused The Quiet Crisis and 1976: Agenda For Tomorrow, in which he spoke about the dangers of urbanism and racial injustice. Accompanied by Frost on a trip to Russia, Udall even visited Premier Nikita Khrushchev to support weapons reduction during the Cold War.

Udall died March 20, 2010 in Santa Fe, NM, one of his favorite places. Years earlier, he had written to his grandchildren, “Cherish sunsets, wild creatures, and wild places. Have a love affair with the wonder and beauty of the earth.”

“Stewart Udall and the Politics of Beauty” will soon be available from Bullfrog Films. For more information, visit bullfrogfilms.com or stewartudallfilm.org.