By David M. Brown

Tiny houses — those less than 1,000 square feet and some much smaller — are big news everywhere.

Tiny homes are the stars of Tiny House Nation on FYI network and are blogged about on smartphones. They’re made of throwaway materials, including railroad container bins that needed a new track, as well as state-of-the-art components that are out of budget for most. They are built lakeside and oceanside, in the mountains and in the desert. They’re tiny but everywhere. Spur, Texas, has even declared itself “tiny house friendly,” without much of a fight from anyone.

And, last month, a documentary about this housing trend, TINY: A Story About Living Small, showed at Valley Art Theater in downtown Tempe.

For the tiny housers who live in these small spaces, the reasons are varied: a commitment to sustainability and energy savings; avoiding consumerism; money savings from living in less space; and a Thoreauvian simplifying, reducing waste and ridding oneself of the excesses of civilized life — “to live life with less,” says Michael L. Schoon, assistant professor in the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University.

“Tiny houses can be built very affordably, they offer a surprising amount of comfort and livability in a small space, and they can be a wonderful sustainability platform — both in the use of green technologies and in enabling a very small ecological and carbon footprint,” Schoon says.

MausHaus and Microdwellings

Recently, Schoon mentored five Arizona State University graduate students in building MausHaus, a 112-square-foot solar-powered mobile house that sleeps four.

“The project went from idea to reality in 100 days,” he explains. Construction began in February and continued through early May before the summer break. “The goal was to create an efficient but welcoming structure to teach local students about minimalist living as well as provide a laboratory for future grad student projects.” Two students received their master’s degrees from the project; one in sustainability, the other in engineering.

Built predominantly with recycled and donated building materials acquired through craigslist.org, MausHaus (affectionately, “mouse house”), when complete, will have a loft and a living room; full shower with on-demand hot water; solar power for all electrical needs, including battery backup for nights; a composting toilet using no water; and counter space for a toaster oven, a stainless steel sink, electrical stovetop burners and a dorm-sized fridge.

The walls, floors and roof are built with structural insulated panels, which are styrofoam sheets attached to oriented strand board (similar to plywood). These have a high insulation rating, thereby reducing energy costs. In addition, the windows are dual-paned low-e versions, allowing sunlight without excessive heat gain. Furnishings will be as green as possible.

“It is an amazing example of sustainable living,” Schoon says. The finished project will be used for educational outreach through ASU’s Sustainability GK-12 programs, promoting a number of features that can be incorporated in construction projects. And, when not on display, the MausHaus group hopes to rent it, he notes.

The project was funded by a Kickstarter campaign which raised more than $4,000, a $1,500 grant from Graduates in Integrative Society & Environment Research (GISER) at ASU, and by the family of Jared Stoltzfus, a doctoral student in the School of Sustainability.

“Still a work in progress, but I hope it eventually feels like a cozy home that just happens to be sustainable,” says Stoltzfus, who for the past two years has worked with area high schools on sustainability education through the National Science Foundation GK-12 Program at ASU. “While I hope to show that people don’t need giant homes to be happy, I also want to highlight what everyone can do in their own homes to make them more sustainable,” continues Stoltzfus, a Virginia native and Arizona resident who is married with two children.

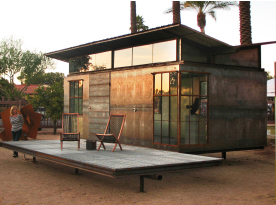

One Phoenix resident, Patrick McCue, sponsors an annual show that features various styles of microdwellings that are 600 square feet or less and modular or portable for ease of shipping and assembly.

Earlier this year, his second show at the Shemer Art Center in Phoenix attracted 10,000 visitors during its six-week run, allowing them to walk into the structures and experience them firsthand. “I want the annual show to bring ideas and people and products together, especially for city infill projects as well as for anyone interested in sustainable housing,” McCue says.

In addition, McCue wants to encourage people to build an actual structure and get experience in building. “I am just not satisfied with the trend in architecture to use computer-generated virtual renderings. I want to grow the microdwelling show to showcase all types of small, sustainable, affordable housing as well as other types of smart use work spaces.”

“Microdwelling 2015” returns to Shemer Art Center next February for five weeks and will feature lectures as well as alternative displays that relate to alternative power and solar cooking. On the weekends, attendees can meet the builders and listen to discussions about the build process of the displayed structures.

Smaller spaces, easier living

Sustainability and budget are two motivations for tiny houses, but those involved talk passionately about downsizing from a philosophical perspective, ridding themselves and loved ones of clutter and gewgaws, space fillers and space that just

fills space.

Cynthia, a Phoenix resident with a psychology degree but who is an architect at heart, is planning to build a livable, inexpensive and beautiful microdwelling. She’s designed one with about 300 square feet, including a Murphy bed that will double as a couch; a small kitchenette with a sink and refrigerator; a living area; a bathroom with toilet and shower; and a fireplace/oven that is open on three sides, two indoors and one to the patio.

She is creating the blocks that will be used for the structure, which she calls “transpaque cubes” because they allow light to pass through but also provide for privacy.

“To me, a microdwelling must be cozy, functional and a place you or I could really live in,” she says. “I think mine would make for a jovial place to chat, get some shade and enjoy some s’mores or pizza with cocktails.”

Sandy, a former airline employee who was transferred to San Francisco from Denver three years ago, downsized from a 980-square-foot two-bedroom, two-story townhouse to a 300-square-foot cottage with only two rooms — a bedroom with a shower stall and a closet-like space for a sink/toilet, and a living room with a full kitchen.

“I have a chaise lounge for reading, a small desk and a laptop stand on wheels that I roll over to my chaise lounge when I feel like chilling out and watching a movie on my laptop,” says Sandy, a full-time student who works as a behavioral tutor for autistic children. “I had to sell about three-quarters of my belongings because this cottage was all I could afford to rent in the Bay Area. At the same time, it felt so liberating to rid myself of all this unnecessary ‘stuff.’ Who needs four different sets of bedding?” Sandy continues.

“The joy about living in a tiny space is that you are forced to buy only what you need, not what you want, and it’s a wonderful feeling! And, you find innovative ways to be even more compact.”

Emotional well-being has come with tiny living, says Sandy, who hopes to buy a piece of land on the coast and build or buy a tiny home after she obtains her degree. “Without so much clutter surrounding you, you actually tend to feel more open and relaxed. Everything has to have its place; otherwise, you’re tripping over it, so it forces you to be more organized.”

Her cat, Sola, has found all the nooks and crannies to explore and seems felinely content, too. “She thoroughly enjoys sitting in the window,” Sandy says, “just being a cat and harassing the birds in my landlady’s backyard.”

For more information, see themaushaus.com, microdwelling.net and rocketfab.com .

David Brown is a Valley freelancer azwriter.com

Photos courtesy of MicroDwell.