BY AIMEE WELCH

A baby born in the United States today has an average life expectancy of just over 78 years. A baby born on the same day in Nigeria has an average life expectancy of only 47 years. It’s 2011—how is that possible? While genetics, ethnicity, political and socioeconomic factors weigh heavily on the statistics, the environmental impact on global health is becoming increasingly evident.

A baby born in the United States today has an average life expectancy of just over 78 years. A baby born on the same day in Nigeria has an average life expectancy of only 47 years. It’s 2011—how is that possible? While genetics, ethnicity, political and socioeconomic factors weigh heavily on the statistics, the environmental impact on global health is becoming increasingly evident.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 13 million deaths could be prevented every year by making our environment healthier. In fact, WHO reports that nearly one quarter of all deaths and of the world’s total disease burden can be directly attributed to the environment. Those are alarming numbers, and a crucial reason why human health and environmental health are two of the most significant issues of our generation and, most likely, for many to come. Regardless of where we live, our health is intricately intertwined—for better or worse—with our own environment.

What, exactly, are these “environmental” factors that are making us sick…or even prematurely dead? That depends on where you live. In developing countries, people are getting sick or dying young from infectious diseases caused by contaminated drinking water, the polluted air from the solid fuels they must burn to cook and stay warm, or malaria; whereas in the United States, our biggest problems are non-communicable diseases like heart disease, cancer and diabetes, to name a few. Diseases that are related to our very own behaviors and shaped, in part, by our direct environment. And these “lifestyle” diseases, while preventable in most cases, are harder to figure out.

Why, despite a greater understanding of risk factors, are incidences of many of these diseases continuing to climb? What is it about the American lifestyle that makes us the most obese nation on the planet? Why, despite nine months of optimal weather conditions, does Arizona rank 35th for obesity rates? And what factors make lower-income people more susceptible to many of these diseases? So many questions, so few answers.

Lifestyle diseases differ from infectious diseases in that they are diagnosed after decades of exposure to potential risk factors ranging from genetics to lifestyle choices, making it hard to pinpoint one cause. What we do know is that diet and exercise have a lot to do with it, and that the solution isn’t as black and white as it seems. Changing individual behaviors is the obvious, but what about the outside influences that impact these behaviors—are our neighborhoods safe, and conducive to walking and biking? Are healthy foods readily available and affordable? Are we seeing (or able to see) a doctor as often as we should? That depends on where we live and, ultimately, the choices we make. And making healthy choices is easier for some than others.

We are Products of Our Own Environment

In the U.S., heart disease, cancer and stroke kill more people than any other cause, and obesity is at epidemic proportions. Why? Because we are consuming sugary, processed and fatty foods, working too much, sleeping too little, driving our cars instead of walking, sitting in front of computers and TVs instead of playing outside, and smoking and drinking more than we should. These are cultural behaviors intertwined into the core of our being. Everyone’s doing it…sadly, we are becoming products of our environment.

When it comes to making a connection between health and the environment, there’s still a lot we don’t know. But here’s what we do know: Eating fruits, veggies and fish can lower our risk of heart disease, stroke and cancer. High cholesterol, raised blood pressure and obesity are linked to a bunch of diseases. Exercise is good for our cardiovascular systems and our mental health. Smoking and drinking too much is bad. A few simple “rules” we could implement into our lives that would make a difference. Easy, right? So why isn’t everyone healthy? Is it because we don’t care, we aren’t following the healthy rules, or is it inconvenient?

Part of it could be that the behaviors that could make us “well” aren’t equally accessible to everybody. Unlike our European and Japanese counterparts, our cities are more spread out, and our definition of “fast food” isn’t an apple and cup of yogurt from the vendor on the corner…

Some countries/states/cities are simply better at implementing infrastructures that accommodate healthy lifestyles, and some people have a much easier time accessing them. And that sometimes boils down to different factors like culture, income, race and ethnicity. But it’s a tangled web, and suggesting why one place is “healthier” than another is like comparing apples and oranges. It is safe to say, however, that people who follow the recommended “rules” for good health are generally healthier than those who do not, no matter where they live.

Why are Some Places Healthier than Others?

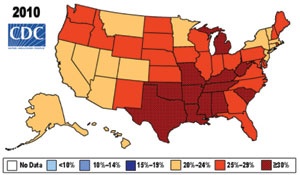

Considering the statistics, it’s not hard to figure out why people in Arizona live longer than those in Zimbabwe. After all, we only have to walk ten feet to a faucet to get clean water, our local media alerts us to stay indoors when the air is too dirty, and fresh fruits and vegetables are readily available. Yet within the U.S., not all diseases are distributed equally. Obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease and a plethora of other conditions seem to travel together, and consistently hit states in the South harder than anywhere else in the country.

In 2010, no U.S. state had an obesity rate below 20%, according to the CDC. And more than 12 states had rates above 30 percent (for comparison sake, Japan’s rate is 3.2 percent). Not unlike statistics for many other lifestyle diseases, the South fared the worst, registering nine of the ten states with the highest rates—Mississippi weighing heavily at the top for the seventh year in a row. The “skinnier” states included Colorado, Utah and Nevada to the west, D.C. and Connecticut in the Northeast. There’s a great divide, and obesity is just one example— as a rule, states in the Northeast and Southwest tend to be healthier with regards to most lifestyle diseases.

So what is making the difference? Are people in those southern states not following the “rules”? What are the healthier states doing correctly? One answer doesn’t fit all, but the usual suspects—income and education levels, racial and ethnic populations, physical activity levels, and other lifestyle habits—often tell the same story.

Research shows that racial and ethnic minority adults, less educated, and lower-income families have poorer health. And some states have a higher percentage of families who fall into those categories. It’s not necessarily that the less fortunate don’t want to be healthy; it’s often easier, and more affordable, not to be.

Adrienne Udarbe of the ADHS Bureau of Nutrition and Physical Activity says many Arizona families are limited to shopping at corner stores or convenience stores that typically don’t have a large supply of fresh foods, and they don’t have access to parks or playgrounds, resulting in limited opportunities to be physically active. “Many rural communities throughout Arizona have high rates of food insecurity and lack of access to healthy foods, or lack of sidewalks to walk to school and work. ADHS encourages these rural communities to work with their local government and communities leaders on innovative approaches to make the healthy choice the easy choice,” she said.

The 2010 Census showed that Arizona’s poverty rate of 18.6 is one of the highest in the country, well above the national poverty rate of 15.1 percent. Arizona also had one of the highest percentages of residents without health insurance, a Hispanic and Latino population nearing 30 percent, as well as a significant Native American population—that’s a lot of risk factors.

That doesn’t necessarily mean money buys happiness, but perhaps it buys some of its key ingredients—good health via high-quality healthcare (one billion people in the world, and 46 million in the U.S. are uninsured); clean water; healthy food; enough time and a safe place to exercise; and the lower stress levels and higher immunity to illness that comes with the privilege of having options over where we work and what we feed our families.

Percent of Obese (BMI > 30) in U.S. Adults

Source: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data/trends.html

Home, Moderately Healthy, Home

As for Arizonans, we have our ups and downs on the nation’s subjective “quality of life” scale, but typically fall somewhere in the middle in terms of life expectancy and many other non-communicable diseases and risk factors attributable to our behaviors and surroundings.

On the “up” side, a recent study conducted by the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) determined that Arizona’s cancer incidence rates are the lowest in the nation. Something in our water? In the air? Our behaviors? We can only speculate, according to Wayne Tormala, bureau chief for the Bureau of Chronic Disease. “It is hard to correlate Arizona’s low cancer rate with some environmental factors because the environment can and has changed over the years. Also, a significant portion of Arizona’s population is highly transient which would have been exposed to the environment in other states. The low cancer rate is more likely attributed to Arizona’s low tobacco usage rate (15 percent in 2010) and the number of individuals leading active lifestyles. These active lifestyles could be attributed to the climate where many individuals stay active year-round,” he said. Despite more than 300 days of sunshine every year, even Arizona’s skin cancer rate is 21 percent below the national average. Tormala surmises it may have something to do with our state’s strong prevention and educational campaigns focused on sun safety.

In addition, Tormala said Arizona hasn’t seen as large of an increase in lifestyle diseases as the rest of the country. He attributes it to the active lifestyle of Arizonans—more than 49 percent of whom exercise regularly, according to a 2009 survey. “Typically the U.S. Southwest is healthier than other parts of the country, such as the Southeast,” he said.

On the “down” side, our air quality regularly puts Metropolitan Phoenix at the bottom, and sometimes dead last, in national clean air rankings. Diane Eckles, office chief for the Office of Environmental Health, says air quality is Arizona’s number one environmental concern over the next 25 years.“Air quality can impact asthma, cardiovascular diseases and pulmonary diseases. It is hard to control in Arizona and is impacted by human activity as well as weather. One of the biggest contributors to poor air quality in Arizona is vehicle emissions. Dust particulates are also very hard to control as evidenced by the extreme dust storms we have had this summer,” she said. Considering air quality is linked to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the fourth leading cause of death in the U.S. and the leading cause of hospitalization in adults…the immediate threat to our health is, in fact, our air.

But some things are even scarier than the brown cloud. According to Tormala, chronic diseases will be Arizona’s biggest health challenge over the next two decades. He said incidence rates for cardiovascular disease and diabetes are on an upward trend across the country, including an increasing amount of younger individuals developing a variety of chronic diseases. “While many of these conditions are manageable, oftentimes those with the condition neglect to do so, leading to increased healthcare and poorer quality of life,” he continued. Among those preventable conditions is obesity, which is reaching epidemic proportions for adults and children nationwide. Udarbe said, “Overweight and obesity contribute to the increases in chronic disease. The only way to combat this epidemic is through a collaborative approach to engineer health back into our everyday lives.”

The Bigger Picture

The concept of “health and wellness” has become a global behemoth and, in our quest for higher-quality, longer, more prosperous living, we’re learning some difficult lessons about the world, and about ourselves. First and foremost, we’re not doing a very good job at staying healthy. Globally, 36 million people die each year from largely preventable, non-communicable diseases like heart disease, stroke, diabetes, cancer and chronic lung diseases; obesity is on the rise; childhood poverty and inadequate healthcare still plague even the wealthiest countries; and millions of people (primarily children) in tropical and third-world countries are still dying needlessly from malaria, diarrhea and HIV/AIDS.

As for the health of our environment, we’re doing better in some areas than others. Our lifestyles are still contributing to the degradation of our planet, and the natural resources the human race will rely on for generations to come. The quality of our water, air and soil—at home and on every continent—should be, frankly, scaring the pants off of us. We’re all a part of the bigger picture. For the majority of people in developed countries, the availability and quality of these resources isn’t yet considered a matter of life and death (at least not immediate death, anyway); but with a world population projected to grow from 7 billion to 9 billion by 2044, we have a lot of work to do to make sure we conserve our resources.

So if we’re really products of our environments, some of us are certainly better off than others. But whatever our circumstances and wherever we are, we can make good choices. You don’t have to move to Japan to get skinny, and Mississippians aren’t destined to be obese. When it comes to living a healthy life, our very own behaviors determine which statistics we’ll become. Salud!