BY AIMEE WELCH

“Give a man a fish and you feed him for a day. Teach a man to fish and you feed him for a lifetime,” so the old proverb goes. Today, teaching a man to fish means something completely different than it used to ─ today, in the midst of an alarming decline in the world’s marine fish population and a burgeoning global population expected to reach 9 billion people by 2050, we have to examine and understand humans’ role in the health of our oceans and their inhabitants ─ past, present and future. We have to learn to fish better…more responsibly…more sustainably.

the midst of an alarming decline in the world’s marine fish population and a burgeoning global population expected to reach 9 billion people by 2050, we have to examine and understand humans’ role in the health of our oceans and their inhabitants ─ past, present and future. We have to learn to fish better…more responsibly…more sustainably.

In a era when destructive fishing practices like bottom trawling and gillnetting regularly make headlines for destroying coral reefs, and killing dolphins, endangered sea turtles and other non-targeted marine animals; overfishing and pollution continue to diminish fish stocks; and illegal “pirate fishing” produces an estimated 25 percent of the fish consumed around the world, many experts believe the industry is far from “sustainable.”

With perilous dismissal, many people simply assume our vast oceans and the mysterious creatures beneath the surface will somehow prevail, in spite of our actions. Why should we care? For starters, oceans cover nearly three-quarters of the Earth, hold 97% of the planet’s water, produce 70% of our oxygen, and absorb carbon from the atmosphere ─ it’s the lifeblood of humankind. Coastal communities from the U.S. to China rely on the fishing industry for economic security and employment. Oceans are also a critical source of food and water for many people around the world ─ the World Wildlife Federation (WWF) reports that, today, approximately 950 million people around the world rely on fish as their primary source of protein, and over 200 million people consider it their principal livelihood…and that’s just for starters.

Yet today, according to Monterey Bay Aquarium, approximately 85 percent of the world’s fisheries are fully exploited, overexploited or completely collapsed.

Where did all the fish go?

While fishing has always had some kind of impact on the marine environment, the pressure caused by industrial-scale fishing was far more detrimental. Similar to the farming industry, fishing experienced rapid growth and change as the industry became commercialized. Small, artisan fishing companies watched as their industry…their livelihood…changed before their eyes.

In the 1950s, an international effort was launched to make protein-rich foods like fish more accessible to more people. Armed with big loans, subsidies and political support, large commercial fleets from around the world combed the oceans, fishing further into the ocean for longer periods of time, using advanced technology like fish-finding sonar, and techniques like long-lining, purse seining, and bottom trawling, which often damaged ocean habitats and scooped up massive amounts of untargeted and unwanted marine animals (or bycatch) along the way. Natural fish populations couldn’t keep up.

It wasn’t until 1976 that the Magnuson-Stevens Fisheries Conservation and Management Act (now known as the Magnuson-Stevens Act) forced foreign fishing fleets to remain 200 miles (versus 12 miles) from U.S. coastlines and established the U.S.’s basic fisheries management system. But the damage had been done and, by the 1990s, the devastating impact was evident.

In 1992, the collapse of Canadian cod stocks off the coast of Newfoundland delivered a devastating blow ─ and a much-needed reality check─to the commercial fishing industry. Despite warnings from scientists and environmentalists, destructive fishing practices and overexploitation of the robust northern cod ─ which had faithfully yielded small-scale fishermen 250,000 tons every year for a century leading up to the 1950s ─ continued until the cod population was so low, the Canadian government had no choice but to close the fishery. A Greenpeace summary of the event says, “They refused to significantly reduce quotas, sighting the loss of jobs as too great a concern. The cost of their short-term outlook and refusal to acknowledge ecological limits was devastating.” No one thought it could happen…but it did, and 40,000 people lost their jobs.

The impacts of overfishing and habitat destruction aren’t only felt at the top of fishing industry’s “food chain.” When the fish aren’t biting, recreational and artisan fisherman are some of the first to know, and many are getting very involved in and passionate about implementing regulations that promote sustainable fishing practices.

Captain Charlie Koski of Island Queen Inland Charters in Chincoteague Island, Virginia, has been taking visitors on fishing trips and nature cruises around the island’s harbor since 2000. For a recreational fisherman whose small business relies on attracting customers with good fishing and beautiful views, sustaining the health of the ocean and fish populations is certainly a priority. “Today, I’m a conservationist,” Captain Charlie says, admitting that wasn’t always the case. He says this fishing season has been a tough one so far, pointing out the drastic difference in his catch between this year and last in his log book. “Something’s going on, and the fish aren’t here.”

Whether it’s the dredging going on for a nearby shoreline restoration project; the draggers that come in and muddy up the waters two weeks before the fishing season starts; weather patterns, or overfishing going on further into the Atlantic…”only a person with a degree in marine biology could possibly answer these questions,” says the Captain. What he knows for certain is that fishing the waterways around Chincoteague is a certainly a different experience than when he visited as a child in the 1960s. He said in those days, after a day on the water, he’d sit around with his Dad talking about their catch ─ how great the flounder fishing had been. What’s changed? Among the global changes that came with the industry’s commercialization, happening out at sea, far from Chincoteague’s quaint fishing village, some differences are in plain sight.

“Draggers are a big impact here. More than anything else,” he says. Since flounder are sight-driven, muddy waters make it tough for them to find food. Today, not only have the number of flounder declined, it’s possible their food source has too. Captain Charlie says many of the flounder he’s catching now have empty stomachs, where they used to be full of the grass shrimp that covered the ocean floor.

Blaming it on the draggers, the dreaded northeast wind, or some other kind of human impact, would only be speculation, but Captain Charlie welcomes new fishing regulations in Virginia, to help fishing get back to the way he remembers it as a kid. “If you want your kids and grandkids to catch fish, you have to have regulations.”

What are we doing wrong?

“Overfishing,” as defined by the WWF is “the catching and killing of more fish than can naturally be replaced.” Simply put, we have too many boats chasing a dwindling number of fish. Overfishing isn’t the only problem our marine ecosystems are facing, but it’s one of the biggest. The WWF reports that the global fishing fleet is 2-3 times larger than what the oceans can sustainably support, and with food demand being the number one reason for overfishing, those facts point to one conclusion ─ the world’s current fishing methods are unsustainable. One 2006 study printed in Science magazine predicts that, unless drastic changes are made to improve the current situation, stocks of all currently fished food species will collapse by the year 2048.

So why is it that, with all the technology and research at our fingertips today, a solution hasn’t been found?

“The international market for fish and fisheries is incredibly complex,” says Amanda Keledjian, a marine scientist with Oceana, the largest international organization focused solely on ocean conservation. Keledjian says issues range from habitat destruction and pollution, to dangerous fishing practices that destroy coral reefs and entangle non-targeted species. Currently, she believes, the world’s biggest metaphorical fish to fry on the path to sustainability is overfishing. “The most important thing is to not take out too much,” she advises, giving a comparison between fishing and a bank account. “If you only take out the interest you’re earning, the principal will keep earning more,” she says. But the fishing industry continues to write checks the ocean can’t cash ─ different countries follow different rules, not everyone follows the rules, there are disagreements over the rules themselves, and fish swim freely from country to country, unaware of any rules. That makes sustainable fishing a tough account to balance.

Without stronger laws and regulations, fisheries and coastal communities around the world will suffer a similar fate, yet it’s still happening. Why? The WWF cites several reasons why overfishing continues to threaten marine biodiversity.

• Poor fisheries management. While the United Nations and fisheries in many countries are now enforcing stricter rules and regulations, issues still exist in relation to adoption of regulations, enforcement of the rules (especially with activities that happen unbeknownst to regulators), and the effectiveness of the fishing limits being set ─ fisheries don’t always follow scientific advice with regards to catch limits. Additionally, customs agencies and retailers aren’t always verifying the source of the fish they’re purchasing to ensure it was caught legally and sustainably. This leads to consumers unknowingly supporting pirate fishing with their seafood purchases.

• Massive bycatch. Bycatch refers to marine animals that are unintentionally caught during the fishing process for another type of fish. It is a huge, global problem, with an estimated 16 million tons of fish wasted every year, as well as sharks, dolphins, whales, turtles, seabirds and other marine animals. These animals are scooped up in shrimp trawlers, caught on long-lines that can measure up to 50 miles in length, and drowned in massive abandoned nets, drifting in the sea. They’re mercilessly discarded by the ton, every year, in nearly every fishery.

• Pirate fishers. Fishermen who ignore fishing laws, regulations and agreements are known as pirate fishers or poachers. Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated fishing (IUU) not only contributes to overfishing, it creates massive amounts of bycatch, hurts the economies of coastal communities that rely on fishing for food, livelihood and economic security, impedes sustainable fisheries, and damages critical marine habitats by using destructive (and sometimes illegal) fishing techniques. Pirates are so good at evading the rules and disguising their crimes that their catch is often sold legitimately into consumer markets around the world, including the U.S.

• Subsidies. Part of the reason commercial fisheries are able to catch too many fish is that they’re enabled by the government. Annual government subsidies valued at more than $10 billion (U.S. dollars)─ typically given in the form of grants, loans or loan guarantees, and tax preferences─ continue to keep too many boats on the water, and give commercial fleets large subsidies that allow them to fish longer, harder and further out to sea away than they would normally be allowed to do.

• Unfair Fisheries Partnership Agreements. In the 1970s, many countries adopted Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ) that prevented foreign fishing fleets from fishing within 200 miles of their coasts. However, Fisheries Partnership Agreements between countries are still made ─ sometimes they benefit all involved, and sometimes they don’t. Because coastal developing countries stand to benefit greatly from “fair” agreements, they often enter to agreements that are ultimately criticized for threatening their very own food security, contributing to overfishing, and preventing the development of local fishing industries. The developed countries on the other end pay only a small fee for rich fishing grounds and don’t effectively prevent illegal fishing by their fleets.

• Destructive fishing practices. When fishing gear or techniques are used the wrong way or in the wrong environment, they can cause irreparable harm to slow-growing ocean habitats such as coral reefs, and kill a devastating quantity of non-targeted marine animals. Some methods are undeniably destructive, like cyanide poisoning and dynamite, and often take place in undeveloped countries where education and money are greatly lacking, or in Asian countries, where consumer demand for high-end fish seemingly trumps ethics. Globally, bottom trawlers and dredgers are considered the most damaging fishing methods. They scrape the sea floor in search of shrimp, cod, flounder, rockfish, scallops and clams using heavy nets that destroy everything on the ocean floor and create massive amounts of bycatch.

Senseless slaughter

And then there are the practices for which reason simply doesn’t apply. Shark finning, for example. It’s not accidental. It’s not incidental. It’s intentional, ruthless and heartless. An unknown number of our oceans’ top predators are caught, their fins are cut off, then they’re thrown back into the ocean, helpless, to die. Why? For soup ─ $100-a-bowl soup, which is a popular dish among the wealthy in places like Hong Kong. “This brutal practice, outlawed in U.S. waters, is not regulated on the high seas or in most nations’ territorial waters. Fins can command $200 a pound in Asian markets, whereas shark meat yields fishing fleets no more than 1 percent as much revenue per pound,” according to a recent article in ScienceNews. Alarming. Unbelievable. But as long as consumers will pay for it, change won’t come quickly.

Illegal whaling is another newsmaker, especially since Animal Planet’s successful “Whale Wars” television series shined a spotlight on illegal whaling, which continues to lead to the slaughter of thousands of whales for profit, despite the International Whaling Commission’s (IWC) 1986 moratorium on commercial whaling. As is the case with overfishing, whaling is big business in Japan, Iceland, and Norway ─ wrought with politics, money and crime ─ and enforcement is a challenge. Conservation organizations like the Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, founded and led by Greenpeace co-founder Paul Watson, travel the high seas, using whatever methods necessary to enforce international conservation regulations and stop illegal whalers in the act. The Japanese, according to Sea Shepherd, kill whales for big money, justifying their actions with the argument that people have always hunted for whales ─ that it’s their right. Sea Shepherd couldn’t disagree more, based in part on a much deeper perspective about these hunted animals, as stated on its website. “Whales are highly social beings and they have a complex form of communication with each other which can only be defined as language. We simply do not understand what those large brains have evolved for, but indeed large brains they have, and large brains suggest that there is a reason and a use for this development.”

Sadly, in some cases human actions aren’t just a matter of ignorance, but of greed and deep-seated entitlement. But saving the oceans is a passion for many people around the world and, with rising disdain emerging for those who disrespect our beloved sea and its inhabitants, change is surely gonna come…

Teaching a Man to Fish…Responsibly

According to Keledjian, re-teaching man to fish responsibly will include some important changes over the next decade or two, including improvements in fishing gear technology to reduce bycatch, better reporting systems, the promotion of renewable ocean energy, and eliminating the bad subsidies that facilitate overfishing. She believes progress is being made, especially in U.S. fisheries management.

In a 2012 feature story about the state of the world’s fisheries, Eric Schwaab, The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) assistant administrator for fisheries, wrote, “We have come a long way since 1976 when our nation’s fisheries were being decimated by uncontrolled overfishing by foreign fleets. Thirty-five years later, we now stand at a point in history when the U.S. model of fisheries management has evolved to become an international guidepost for sustainable fishery practices.” Schwaab is referring to the fact that 2012 marks the first year that annual catch limits (ACLs), which set limits on the number of fish (by species) that can be caught over the course of a year, will be enforced in the United States. ACLs are considered in the industry to be one of the strongest conservation measures of the Magnuson-Stevens Act, and the U.S. is the first country to impose ACLs for every species under its management. The Marine Fish Conservation Network is just one of many organizations that believe this accomplishment to be monumental, stating, “The result is a one-of-a-kind fisheries management system that has the potential to change the way the world fishes.”

The NOAA Fish Watch declares, “Seafood is sustainable when the population of that species of fish is managed in a way that provides for today’s needs without damaging the ability of the species to reproduce and be available for future generations.”

So if the progress made in U.S. fisheries can effectively “change the way the world fishes,” and create truly sustainable seafood, we’re on our way ─ but getting there will require fighting through some rough waters. The challenges of maintaining our marine ecosystems run deep, and finding solutions relies on the support of fishermen, conservation organizations, government, businesses and consumers around the world. Ultimately, if we learn to fish in a way that supports the world’s oceans, lakes and waterways, we’ll make a difference during our lifetime and for generations to come.

What can you do to support sustainable fishing?

• Support retailers that sell sustainable fish (like Whole Foods and Walmart)

• Buy Certified Sustainable Seafood (MSC label)

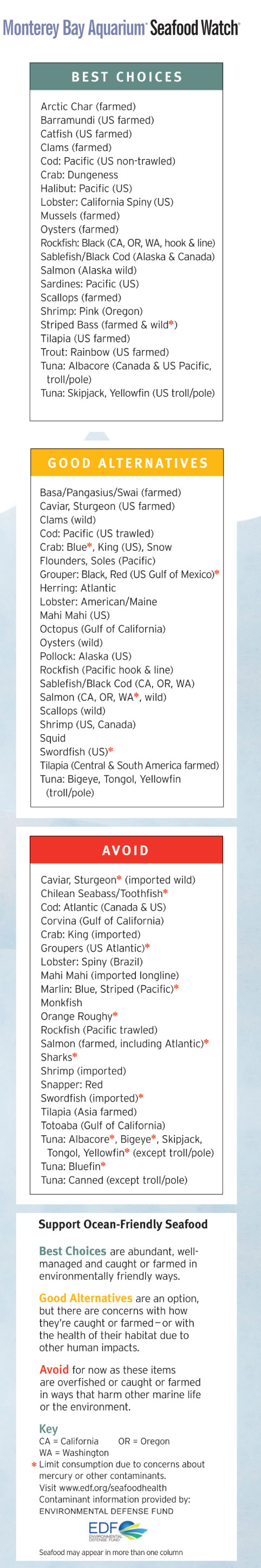

• Eat only fish that are raised/fished sustainably (see Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch® Pocket Guides below)

• Request sustainable fish from your favorite restaurants

• Support ocean conservation organizations

To download the full Pocket Guide from the Monterey Bay Aquarium’s Seafood Watch® program, visit montereybayaquarium.org.

SOURCES:

Food and Agriculture Association of the United States

fao.org