From October 31 to November 12, 197 countries met in Glasgow, Scotland, to attend the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference, better known as COP26. It was the 26th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), the third meeting of the parties to the 2015 Paris Agreement.

COP26 is the latest and one of the most important steps in decades with the UN-facilitated efforts to help ward off a climate emergency.

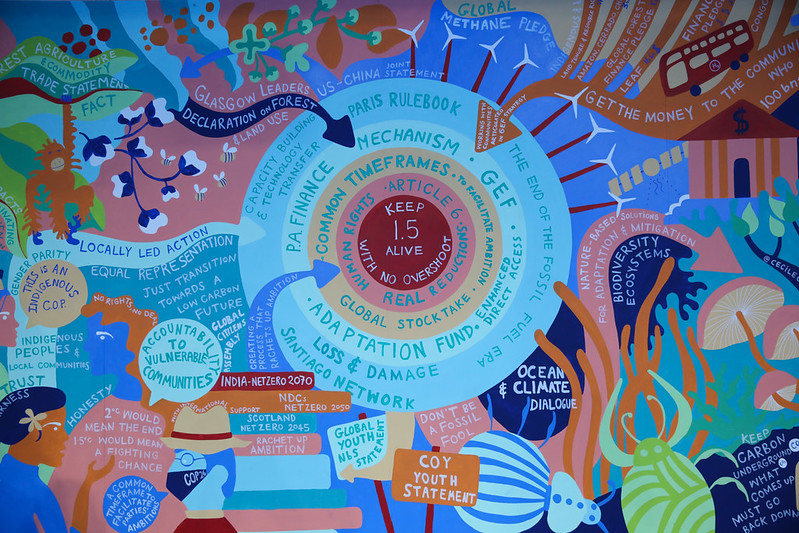

“It is an important step, but it is not enough. We must accelerate climate action to keep alive the goal of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees,” said António Guterres in a video statement released at the close of the two-week meeting.

The UN chief added that it is time to go “into emergency mode,” ending fossil fuel subsidies, phasing out coal, putting a price on carbon, protecting vulnerable communities and delivering the $100 billion climate finance commitment.

“We did not achieve these goals at this conference. But we have some building blocks for progress,” Guterres said.

The outcome also firms up the global agreement to accelerate action on climate this decade. The UN climate summit delivered on its primary goal of keeping alive the Paris Agreement’s aim to limit global warming to 1.5°C (2.7°F) above pre-industrial levels. Nations agreed on the Glasgow Climate Pact, which states that carbon emissions will have to fall by 45 percent by 2030 to keep alive the 1.5°C goal.

The data is unequivocal: climate change is widespread, rapid, intensifying and already impacting every region on Earth, both on land and in the oceans. It is imperative that the nations work together. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the NDC Synthesis Report and the Emissions Gap Report all tell us, however, that we’re not on that path.

The objective of the IPCC is to provide governments at all levels with scientific information that they can use to develop climate policies.

In 1992, the UN organized a major event in Rio de Janeiro called the Earth Summit, in which the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change was adopted. In this treaty, nations agreed to “stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere” to prevent dangerous interference from human activity on the climate system. Since 1994, when the treaty entered into force, the UN has been bringing together almost every country on Earth for global climate summits.

This year should have been the 27th annual summit, but because of COVID-19, the 2020 conference was canceled.

The conference heard many encouraging announcements:

- One of the biggest was that leaders from over 120 countries, representing about 90% of the world’s forests, pledged to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030.

- There was also a methane pledge, led by the United States and the European Union, by which more than 100 countries agreed to cut emissions of this greenhouse gas by 2030.

- More than 40 countries – including major coal-users such as Poland, Vietnam and Chile – agreed to shift away from coal, one of the biggest generators of CO2 emissions.

- Regarding green transport, more than 100 national governments, cities, states and major car companies signed the Glasgow Declaration on Zero-Emission Cars and Vans to end the sale of internal combustion engines by 2035 in leading markets, and by 2040 worldwide.

- At least 13 nations also committed to end the sale of fossil fuel-powered heavy-duty vehicles by 2040.

- Over 450 financial institutions overseeing $130 trillion in assets promised to align their portfolios with the goal of achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

Countries made notable commitments in the Glasgow Climate Pact, but they still fell short of the action needed to keep global warming within manageable levels. However, there are provisions to increase transparency with the aim of boosting accountability. The pact also urges nations to come back in 2022 with greater ambitions.

COP26 President Alok Sharma had urged negotiators to “consign coal power to history,” but that didn’t happen. Despite the historic call in the Glasgow Climate Pact for a “phase-down” in coal power, some coal-reliant countries have indicated that they will not completely stop using coal until the 2040s or later.

Countries also failed to make significant progress on climate finance. The UN Environment Program estimates that developing countries need $70 billion per year for adaptation, and this figure is expected to double by 2030. Going into COP26, poorer nations renewed their calls for financial help from richer nations to adapt to the effects of climate change. They also sought to establish a loss-and-damage fund for developed countries to compensate developing countries for areas irreparably harmed by climate impacts.

But after resistance from the United States, the European Union and other rich nations, the accord failed to secure funds for that compensation.

In closing remarks at the summit, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres recognized what he called the “climate action army.” Guterres acknowledged the power of activists to propel governments and companies beyond words and into action. He urged them: “Never give up. Never retreat. Keep pushing forward.”

The Glasgow Climate Pact calls on 197 countries to report their progress toward more climate ambition next year, at COP27, set to take place in Egypt.

Keep up with all of Green Living’s original content online and on social media.